Menstrual Health: A Fundamental Right, Not a Privilege

Introduction

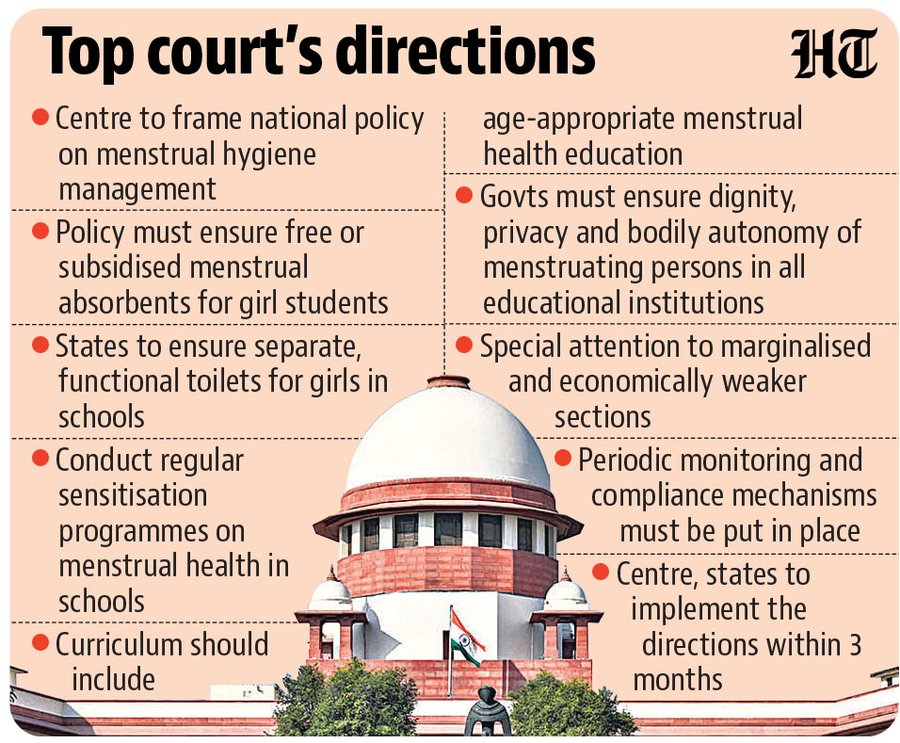

The Supreme Court of India (SC) formally acknowledged menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) as a basic right under Article 21 (Right to Life and Dignity) in the case of Dr. Jaya Thakur v. Government of India & Ors. (2026). The court ordered the Center and states to provide free sanitary napkins and working restrooms in every school through a continuous mandamus, a judicial order that keeps a case pending to monitor compliance.

What did the Supreme Court Rule on Menstrual Health?

- Article 21 (Dignity and Bodily Autonomy)

- Inaccessibility to menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) facilities exposes girls to “stigma, stereotyping, and humiliation,” the Court decided, therefore violating their right to a dignified life.

- It is considered a violation of physical autonomy when forced absences or dropouts occur because of biological realities.

- According to the SC, MHH are essential to leading a dignified life rather than just surviving. The right includes women’s reproductive health, privacy, and physical autonomy.

- Substantive Equality (Article 14)

- It goes beyond “formal equality” (equal treatment for all). It makes the case that “structural exclusion” results from disregarding women’s particular biological demands.

- In order to place girls on an equal basis with their male counterparts, the State must address these particular obstacles, according to the SC.

- Right to Education (RTE)

- The Court held that the term “free” under the RTE Act 2009 does not simply refer to the waiver of tuition costs. It necessitates eliminating every financial obstacle that keeps a youngster from finishing their education, even the price of sanitary items.

- The RTE Act of 2009 made the need for separate restrooms a “substantive” need rather than only an “infrastructural” one. People now call the lack of these amenities a “stark constitutional failure.”

- Accountability & Feedback

- District Education Officers (DEOs) are required to perform routine inspections and, more importantly, gather “anonymous input” from students through questionnaires in order to evaluate the situation on the ground.

- In addition, the Supreme Court requested that the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) or State CPCR supervise the execution of its directives, which stipulate that the Union’s Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School-Going Girls (Classes 6–12) and its directives will function as mandatory pan-Indian standards in addition to current state policies and programs.

- Provision of Products: Both public and private schools are required to have free oxo-biodegradable sanitary napkins available through vending machines.

- Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Corners: Schools must set up special areas with supplies such as extra underwear, uniforms, and throwaway bags to deal with “menstruation-related emergencies.”

- Sanitation Infrastructure: There must always be functional, gender-segregated restrooms with soap and water connectivity.

- Waste Management: The Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules, 2026, require the integration of safe and ecologically responsible disposal methods.

- Male Sensitization: Gender-responsive curriculum at the NCERT and SCERTs was required by the Court. It stated that to stop harassment, males need to be taught about the basic realities of menstruation.

What is the Significance of Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right?

- Establishment of “Biological Citizenship”

- According to the verdict, the State is liable for the “biological tax” that women pay, establishing a new category of rights.

- If a woman’s menstruation or any other natural function disadvantages her, the state must step in to make up for it.

- This shifts from Negative Liberty, where the state will not prevent you from attending school, to Positive Liberty, where the state is required to supply the pads and restrooms so that you can go.

- Redefining the “Free” in RTE

- According to NFHS-5, only 77.3% of women between the ages of 15 and 24 employ sanitary menstruation practices, and over one-fourth do not have access to basic menstrual assistance.

- Due to this deprivation, around 23% of girls experience chronic absence or dropout after puberty, which immediately leads into educational exclusion.

- Acknowledging this connection, the Supreme Court defined “menstrual poverty” as the denial of girls’ equal access to sanitary goods, water, toilets, and safe disposal, which compromises their bodily autonomy.

- The Court makes the RTE substantively enforceable by redefining “free education” as a requirement that is materially enabling rather than just nominal by requiring free sanitary pads.

- Socio-Legal Engineering

- The Court is utilizing the law as a weapon for social transformation by requiring training and sensitization. It acknowledges that one of the main reasons for dropouts is the “hostile atmosphere” that non-sensitive males and male teachers create.

What are the Government Measures to Improve Menstrual Health?

- Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene: Targets teenage females between the ages of 10 and nineteen. It places a strong focus on awareness, sanitary napkin access, and ecologically friendly disposal.

- Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School-Going Girls: Provides gender-segregated restrooms, affordable goods, and disposal facilities. incorporates teaching about menstruation hygiene into the curriculum.

- PMBJP (Pradhan Mantri Bharatiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana): For only Rs. 1 per pad, more than 16,000 Janaushadhi Kendras sell oxy-biodegradable “Suvidha” napkins. Sales totaled about 96 crore pads by November 2025.

- ASHA Network: To overcome social taboos, Frontline employees hold monthly community meetings and give subsidized packs (Rs. 6 for 6 napkins).

- Women & Child Development Initiatives: Mission Shakti (Beti Bachao Beti Padhao), Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK), and the Scheme for Adolescent Girls (SAG) all place a strong emphasis on menstrual health awareness.

- Samagra Shiksha (Ministry of Education): Finances the installation of sanitary pad vending devices and incinerators at educational institutions.

- Swachh Bharat Mission: Outlines National MHM Guidelines for rural regions with an emphasis on cleanliness and behavior modification.

- UGC Advisory: Requires Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to maintain hygienic facilities in prominent places.

What are the Challenges in Implementing the Menstrual Health and Hygiene Guidelines?

- Last-mile infrastructure deficit

- Although there are toilets in rural and isolated schools, it is unclear if they have running water, soap, disposal facilities, or regular vending machine maintenance.

- Facilities deteriorate quickly when there is a lack of specialized cleaning personnel and regular O&M expenditures.

- Procurement and Supply Constraints

- States have significant logistical hurdles in scaling up high-quality, reasonably priced Oxo-biodegradable sanitary pads in a short amount of time.

- Without dedicated funds, MHM spending might put a burden on state education budgets and displace programs like teacher recruiting or midday meals.

- Feedback Authenticity Concerns

- Surveys and grievance procedures may not allow for honest reporting by students due to power dynamics and fear.

- Schools frequently continue to reinforce gender inequalities, treating menstruation as filthy, which causes girls to be embarrassed, stigmatized, and excluded, despite WHO standards and the Ministry of Education’s 2021 mandate on sensitization.

- Unsafe Waste Disposal Risks: Environmental compliance is at risk due to standardized menstrual waste processes and inadequate technical capability for operating incinerators.

What Measures Can Strengthen Menstrual Health and Hygiene?

- Inclusivity: Transgender males and non-binary people who also have periods must be included in the policy.

- Sashaktikaran (Empowerment): State governments ought to support local biodegradable napkin manufacturing by utilizing Self-Help Groups (SHGs).

- Assured Water Supply: Incorporating the Jal Jeevan Mission into school restrooms to provide flowing water around-the-clock, which is essential for menstrual hygiene.

- Privacy-First Design: Toilets should be equipped with mirrors, hooks, internal locks, and “privacy screens” so that females may change their products and wash without worrying about being seen.

- Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) Alternative: The government may look at “Pad Credits” or DBT to the girl’s (or mother’s) account expressly for the purchase of sanitary items in places where the supply chain is weak.

- Disposal as a Service: Menstrual trash is collected and processed by local “Safai Mitras” via the Swachh Bharat Mission (Grameen) to prevent it from ending up in general landfills.

- Standardized Procurement: To prevent the distribution of inferior, plastic-heavy alternatives, states should set up a Centralized Procurement Cell to guarantee that all napkins distributed adhere to the ASTM D-6954 or IS 17518 standards (which are centered on assessing the degradation of plastics in the environment) for biodegradability.

Conclusion

“A period should conclude a sentence, not a girl’s education” is a straightforward yet potent reality that the Supreme Court’s decision provides constitutional meaning to. The ruling paves the way for systemic change, ongoing governmental accountability, and true gender justice by acknowledging menstrual health as essential to equality, dignity, and education.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What did the Supreme Court rule on menstrual health in 2026?

According to this, menstrual health and cleanliness are essential components of the Article 21 right to life, dignity, bodily autonomy, and reproductive health.

How does the judgment link menstrual health with the Right to Education?

The Court determined that the absence of pads or toilets amounts to a constitutional violation and that period poverty is a financial obstacle under the RTE Act.

What key directions were issued to schools?

MHM corners, functioning gender-segregated restrooms, free Oxo-biodegradable sanitary pads, secure waste disposal, and educated personnel are all required in schools.

What role does the idea of “substantive equality” have in this decision?

It acknowledges that the state must actively address such structural barriers and that treating everyone equally overlooks biological disadvantages.

Sources:

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/health-news/menstrual-health-matters-why-menstrual-hygiene-must-be-a-right-not-a-privilege/articleshow/121515996.cms

- https://www.thehindu.com/videos/supreme-court-recognises-menstrual-health-as-a-fundamental-right/article70574140.ece

- https://www.mea.gov.in/images/pdf1/part3.pdf

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10733771/

- https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf/bd47/en/constitution-en.pdf

Leave a Reply