Introduction

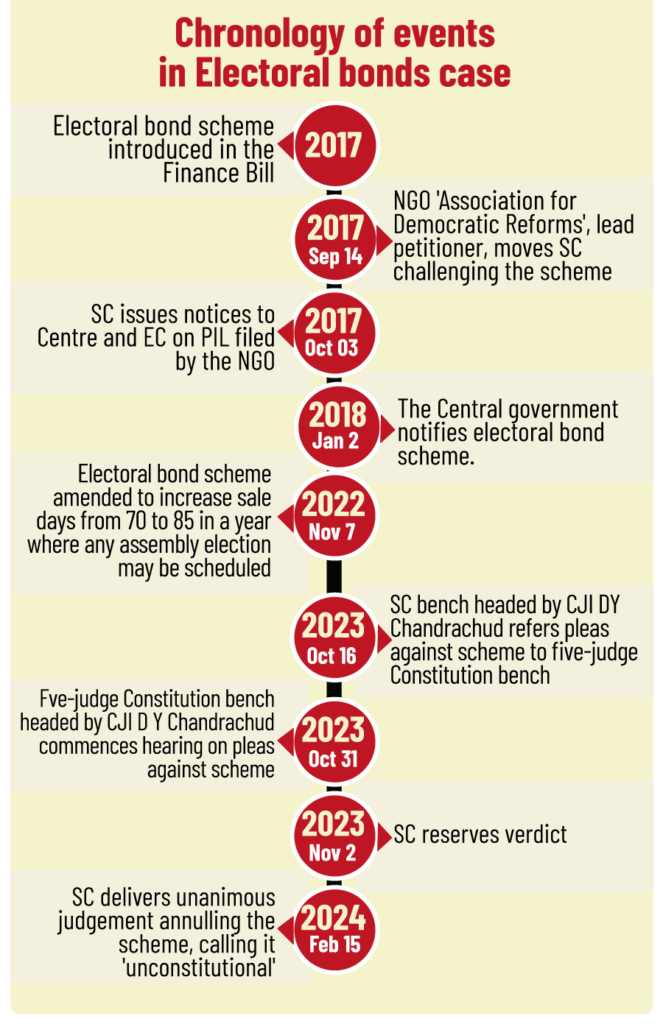

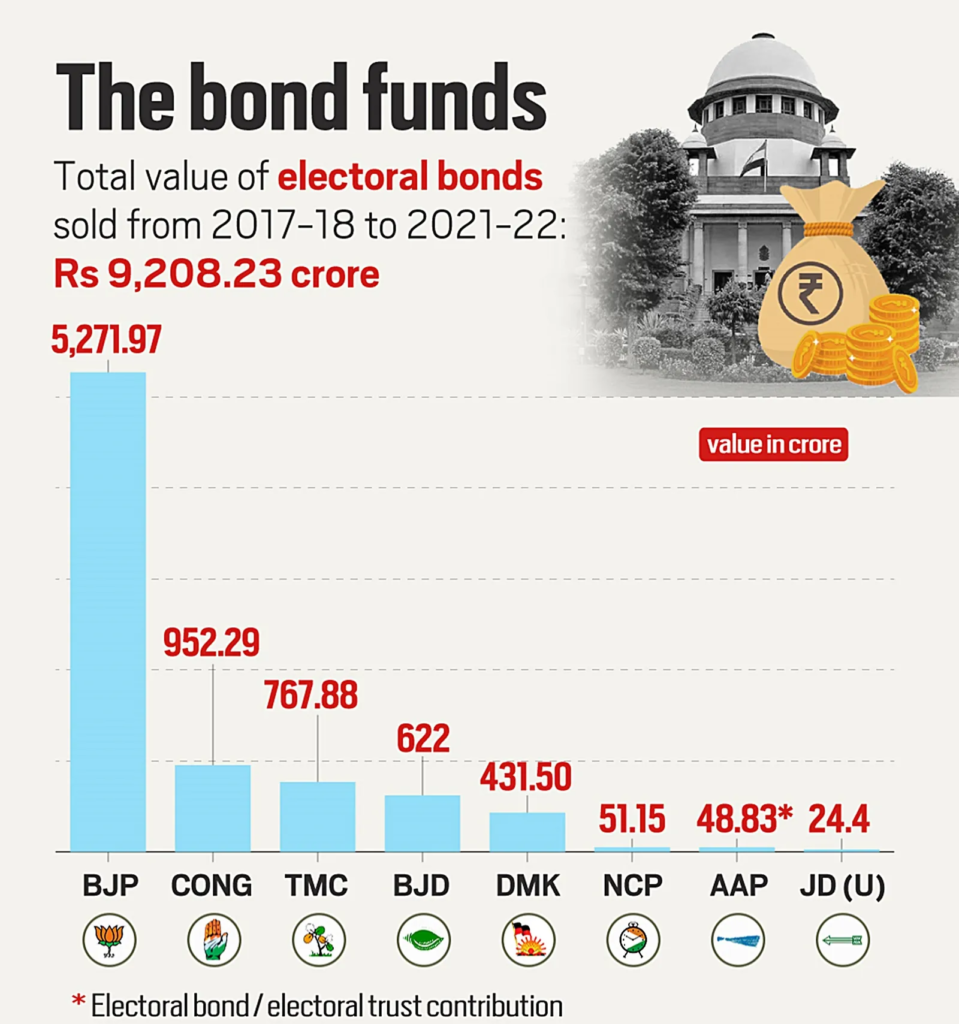

Declaring the electoral bonds system unlawful, the five-member Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court (SC) unanimously upheld every objection to every part of the case. The Election Commission of India (ECI) was given an order for the SBI to immediately cease issuing electoral bonds and to provide all relevant information on the bonds sold, including the identities of all donors and receivers.

What is the Electoral Bond Scheme?

- Electoral Bonds

- Similar to promissory notes, electoral bonds can be purchased from the State Bank of India (SBI) by businesses or private citizens in India. The political party receiving the donation can then redeem the bonds.

- Only the designated account of a registered political party may redeem the bonds.

- Individuals have the option to purchase bonds alone or in combination with other people.

- Electoral Bond Scheme

- To purge political finance in India, the Electoral Bonds Scheme was introduced in 2018.

- Transparency in election finance in India was the primary goal of the electoral bonds program.

- In a nation transitioning to a “cashless-digital economy,” the administration had referred to the plan as an “electoral reform.”

- Amendments Made to the Scheme in 2022

- Additional Period of 15 Days

- Introduced a new paragraph saying that, in the year of general elections to the Legislative Assembly of States and Union Territories with Legislature, the Central Government should specify an extra fifteen-day term.

- When the Electoral Bond Scheme was launched in 2018, these bonds were made accessible for ten days in January, April, July, and October, depending on what the federal government could have decided.

- In the year of the general election to the House of People (Lok Sabha), the Central Government had to set aside an extra thirty days.

- Validity

- The Election Bonds are only good for fifteen calendar days after they are issued, and if they are deposited after that time, no money will be given to the political party that is the payee.

- On the same day, the Election Bond that a qualified political party deposits in its account will be credited.

- Eligibility

- Electoral Bonds may only be obtained by political parties recognized under Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA, 1951) and who received at least 1% of the total votes cast in the most recent general election for the Lok Sabha or State Legislative Assembly.

- Additional Period of 15 Days

Why did SC Reject the Electoral Bonds Scheme?

- Violation of the Right to Information

- The plan violated the basic right to knowledge under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, the court said, by allowing anonymous political donations.

- It emphasized how the strong correlation between money and politics and economic inequality results in varying degrees of political participation. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that making a monetary donation to a political party would result in quid pro quo agreements.

- Not Proportionally Justified to Curb Black Money

- It emphasized that the government did not use the least restrictive approach to accomplish its goal, relying instead on the proportionality criteria established in its 2017 decision in the KS Puttaswamy case, which maintained the right to privacy.

- The court also agreed with the petitioners’ arguments that there is no valid basis to restrict the basic right to information because the goal of combating black money cannot be linked to any of the acceptable constraints specified under Article 19(2).

- Right to Donor Privacy Does Not Extend to Contributions Made

- The court noted that money given to political parties is typically done so for two reasons: first, as a show of support, and second, as a quid pro quo.

- It did, however, highlight the fact that the substantial political donations made by businesses and corporations should not be equated with the monetary contributions made by other segments of the community, such as students, daily wage workers, artists, or educators.

- As a result, the Chief Justice ruled that contributions made to influence policy are not covered by the right to privacy about political membership. It only covers gifts given in the truest sense of political support.

- Unlimited Corporate Donations Violate Free and Fair Elections

- The court determined that the 2013 Companies Act’s Section 182 change, which allowed corporations to make limitless political payments, was blatantly arbitrary.

- Under certain restrictions, the clause permits Indian businesses to donate money to political parties. However significant changes were made with the Finance Act of 2017, one of which was the elimination of the previous limit on corporate donations to political parties, which was set at 7.5% of the average earnings of the three previous fiscal years.

- Furthermore, it was no longer necessary for businesses to reveal the identities of the political parties to whom contributions were made in their Profit and Loss (P&L) statements.

- The Chief Justice emphasized that Section 182 is incorrect in that it treats individual political donations equally with corporate contributions, which are frequently given with the hope of receiving benefits in return.

- Amendment to Section 29C of RPA, 1951 Quashed

- Initially, parties had to report all contributions over ₹20,000 and indicate if they came from corporate or individual donors under Section 29C of the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

- Nevertheless, this clause was changed by the Finance Act of 2017 to include an exception that states donations made through electoral bonds are exempt from this requirement.

- The court struck down the amendment, noting that the initial requirement to reveal contributions exceeding ₹ 20,000 successfully balanced the right to information for voters with the right to donor privacy, particularly since contributions below this threshold were much less likely to have an impact on political decisions.

- Other Observations by SC

- The SBI has been directed to immediately cease issuing any more electoral bonds and to provide the ECI with information on any bonds that political parties have acquired after April 12, 2019, by March 6, 2024.

- These particulars have to contain the date of purchase for every bond, the buyer’s name, and the bond’s denomination.

- By March 13, 2024, the ECI will have posted all of the information that the SBI gave on its official website.

- Election bonds that have not yet been redeemed by the political party and are still within their fifteen-day validity period must be returned, and the issuing bank will then credit the money back to the buyer’s account.

What Issues Regarding Electoral Bonds Were Raised?

- Contradicting its Basic Idea

- The main complaint leveled at the electoral bonds program is that, far from bringing openness to election spending, it does the exact opposite.

- Critics point out, for instance, that electoral bonds’ anonymity only applies to the general public and opposition parties.

- Possibility of Extortion

- Such bonds’ sale through a government-owned bank (SBI) makes it possible for the government to identify the precise source of funding for its adversaries.

- This gives the current administration the ability to either victimize large corporations for not supporting the ruling party or extort money, particularly from them. In any case, this gives the governing party an unfair edge.

- A Blow to Democracy

- The Union government has removed the requirement for political parties to reveal donations made through electoral bonds by amending the Finance Act of 2017.

- As a result, voters will be unaware of the identity and level of funding provided to each party by any particular person, business, or organization. On the other hand, voters choose the representatives of their community in Parliament under a representational democracy.

- Compromising Right to Know

- For an extended period, the Indian Supreme Court has maintained that the freedom of expression guaranteed by Article 19 of the Indian Constitution includes the “right to know,” particularly concerning elections.

- Against Free & Fair Elections

- The citizens are not given any information by electoral bonds. The current government, however, is not protected by the aforementioned anonymity as it may always obtain donor information by requesting it from the SBI.

- This suggests that the ruling party may use this knowledge to sabotage impartial and free elections.

What Are the Ideas for Indian Election Funding?

- Regulation of Donations

- Donations from some people or organizations—such as foreign nationals or businesses—may not be permitted. Donation caps may also be in place to prevent a party from being dominated by a small number of powerful contributors, whether they be people, businesses, or civil society organizations.

- Contribution caps are a common tool used by certain governments to control the influence of money in politics. various categories of donors are subject to various contribution caps under US federal law. Some other nations, including the UK, rely on spending caps rather than contribution limitations.

- Limits on Expenditure

- Spending caps prevent a financial arms race in politics. Even before they begin to fight for votes, they release the parties from the burden of having to compete for funding.

- As a result, several governments set a cap on political parties’ spending. Political parties are prohibited from spending more than Euro 30,000, or around Rs 30 lakh, for each seat in the UK, for instance.

- Legislative attempts to impose spending caps in the US have been thwarted by the Supreme Court’s wide interpretation of the First Amendment (freedom of expression).

- Providing Public Funding to Parties

- The most popular approach is to establish predefined standards. Parties that are important within the political system, for example, are given public subsidies in Germany.

- Membership payments, donations from private sources, and the number of votes they earned in previous elections are typically used to gauge this. Special state financing is provided to German “political party foundations” to support their role as party-affiliated policy think tanks.

- “Democracy vouchers,” a relatively new experiment in public finance, are utilized in Seattle, Washington, municipal elections. To qualified voters, the government distributes a set quantity of vouchers, each with a set value.

- Voters may make donations to the candidate of their choosing with these vouchers. The voucher is financed by public funds, but each voter gets to choose how the funds are distributed. In other words, people get to “vote” with their money before casting a ballot.

- Disclosure Requirements

- The foundation of disclosure regulation is the idea that public scrutiny and the availability of information may affect the choices made by politicians and the votes cast by the people. Mandatory disclosure of party funding isn’t necessarily a good idea, though.

- Donor anonymity might occasionally be beneficial in safeguarding donors. Donors could worry, for example, about extortion or revenge from those in positions of authority. In turn, donors may be discouraged from giving money to causes they support if they fear punishment.

- A lot of places have had trouble finding a suitable middle ground between the two valid worries of openness and privacy. The Supreme Court addressed this matter in its ruling.

- The Chilean Experiment

- Donors may send funds to the Chilean Electoral Service to support parties under the “reserved contributions” method. The Electoral Service would then deliver the funds to the party without disclosing the identity of the donor.

- Even under the best-case scenario, the political party would not be able to determine the exact amount paid by any one contributor, making it very impossible to negotiate a quid pro quo.

- Nonetheless, it would be advantageous for parties (in need of funds) and donors (desiring government favor) to formally coordinate ahead of time to determine the total amounts contributed by those donors. In fact, as many scandals from 2014–15 made clear, funders and politicians in Chile have colluded to undermine the system of total anonymity.

- Balancing Transparency, Anonymity

- Finding a balance between the rightful public interests of transparency and anonymity is one of the most popular approaches. Many regimes achieve this balance by mandating the disclosure of big donations while permitting anonymity for smaller contributors.

- In the United Kingdom, a party must declare any donations from one source that exceed Pounds 7,500 in a given calendar year. Germany’s equivalent cap is 10,000 euros.

- Large contributors are more likely to reach quid pro quo agreements with parties, whereas small donors are more likely to be the least powerful in the government and most susceptible to political victimization.

- Establishing National Election Fund

- Creating a National Election Fund that all donors might contribute to would be an additional choice. Parties might get the money according to how well they performed in the election. This would put an end to the purported worry of contributors taking revenge.

- The potential of political parties misusing funds they get for things like terrorism or violent protests was brought up by the highest court during the hearing, and it questioned the Center about its level of control over the use of the funds.

Conclusion

A momentous day in Indian democracy occurred on February 15, 2024, when the Supreme Court handed down a historic decision invalidating the Electoral Bonds Scheme. The Court unanimously ruled that the plan was illegal, upholding democracy as the cornerstone of the Constitution and taking into account all of the arguments put forth. By this ruling, the government must stop issuing electoral bonds right now and provide the Indian Election Commission with all pertinent data. The Court’s decision emphasizes how the plan violates people’s right to knowledge and disproves the government’s claims, highlighting how the Constitution cannot be interpreted to allow for possible abuse.

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQs)

What is the Supreme Court decision on the electoral bond?

On February 15, 2024, a five-judge panel led by Chief Justice D. Y. Chandrachud ruled that the electoral bonds program was illegal. According to Article 19(1), the plan, which gave political funders anonymity, violated voters’ right to knowledge (a).

What is the electoral bond controversy in India?

The disclosures have intensified concerns that the electoral bond system permitted a quid-pro-quo arrangement between businesses and political parties, resulting in an odor of corruption and extortion, as the 960 million voters in the country prepare for an important national election.

Are electoral bonds legal in India?

After being introduced in 2017, Election Bonds were a means of financing political parties in India until the Supreme Court declared them unlawful on February 15, 2024.

Why did the Supreme Court cancel electoral bonds?

According to the Supreme Court, the Electoral Bonds Scheme infringes on Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution’s guarantees of the right to information and the freedom of speech and expression. Quid pro quo may result from it. The Companies Act modification that permits corporate political sponsorship in its entirety is declared unlawful by the court.

Sources:

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/why-did-the-supreme-court-strike-down-the-electoral-bonds-scheme-explained/article67848657.ece#:~:text=Supreme%20Court%20says%2C%20the%20Electoral,lead%20to%20quid%20pro%20quo.&text=The%20court%20rules%20that%20the,corporate%20political%20funding%20is%20unconstitutional.

- https://indianexpress.com/article/india/supreme-court-hears-sbi-plea-to-extend-deadline-on-electoral-bonds-details-what-steps-have-you-taken-in-last-26-days-9207471/

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/electoral-bonds-sc-dismisses-sbis-plea-for-extension-seeks-details-by-tomorrow/articleshow/108382360.cms?from=mdr

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/electoral-bonds-case-sc-pulls-up-sbi-for-not-furnishing-details-asks-what-steps-have-you-taken-in-26-days/articleshow/108383038.cms

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/breaking-supreme-court-directs-sbi-to-furnish-electoral-bonds-details-to-election-commission-details-by-march-12-101710138259650.html

- https://www.indiatoday.in/law/story/electoral-bonds-sbi-extension-supreme-court-verdict-top-quotes-2513229-2024-03-11

- https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2017/27935/27935_2017_1_1501_50573_Judgement_15-Feb-2024.pdf